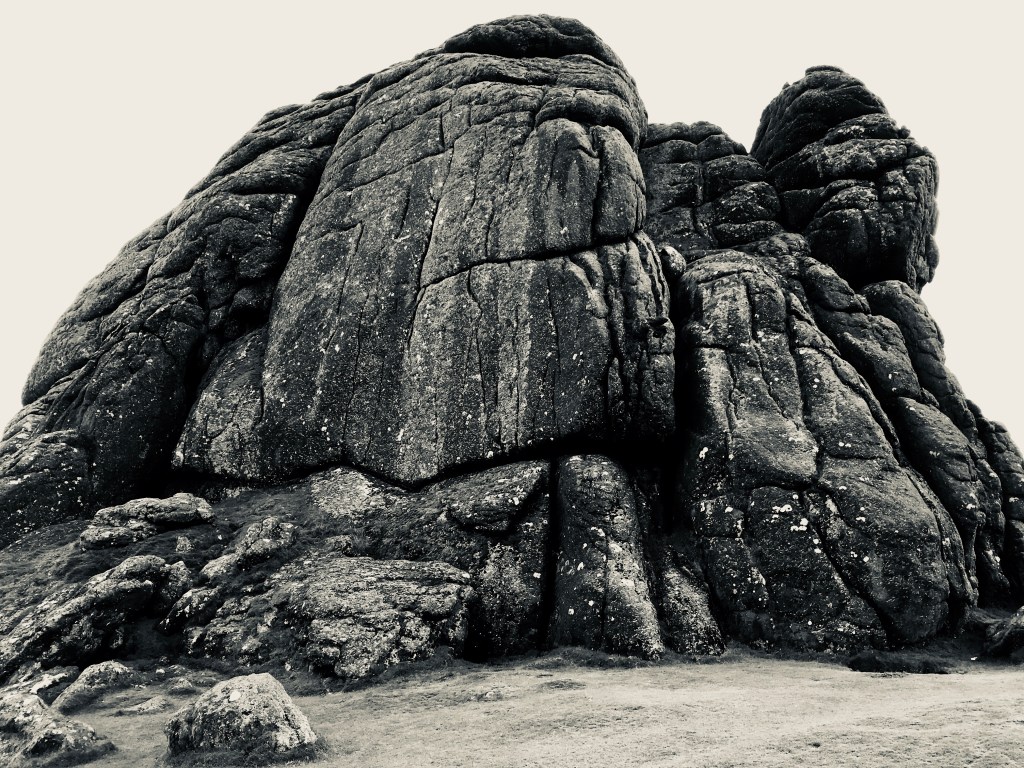

Haytor Quarry, Dartmoor

October 2017

The Bowerman’s Nose was wrapped in a thick misty muffler, bleary granite-cold eyes peering into the bleakness of this autumnal morning. For Dartmoor was dreary, damp and dismal. A smothering fog had descended and all seemed lifeless, hopeless, bland and blinded. I looked about me, but could see no road, no pathway, not even the faintest of tracks to show me the way.

Lost and alone.

Physically and psychologically.

For, thirty years as an ambulance medic and family doctor had finally extracted their inevitable toll. Ninety-hour weeks of pressure and pain, of horrors and heartbreak, had wrung me dry. Taken me to the brink. Burned me out. Hollowed me into a husk – into the fragile shell of a man.

So I did what I always do in distress. I headed to the wild.

To Haytor, sad scene of many suicides.

But not for me. I was here to swim, for swimming is my salve, my healing helper.

And I had read about a quarry here, nestled below the tor, amidst Bronze Age hut circles and century-clinging tin streamworks. Once bustling and busily yielding the stone that built the British Museum and London Bridge, the quarry fell silent in 1858, victim to cheaper Cornish granite.

It is now a haven of solitude.

A place to be alone.

At last, a path – the old granite tramway – linking quarry to canal – forging an irresistible progress through bogland and scrubby grass.

Leading me along the straight and narrow – the road to salvation – to the water and the blessed baptism that awaited me there.

But my initial impressions were not of Paradise, Heaven, Nirvana.

Far from a being a promised land, the discarded debris cast off a rusty hue of abandonment, of leaving in a hurry.

More Mary Celeste than celestial marvel.

A lazy breeze ruffled the surface of grey, slaty water, looking every bit as cheerless as I felt. Laying my clothes on a clammy stone, I caught site of my naked body in a peaty puddle and wondered why, oh why was I here?

Gingerly picking a path through slivers of granite, sharp as flint, I made a hesitant, head-down journey into the lake.

And it was every bit as mortifying as the scene around me. As if the ice-cold hands of long-dead quarrymen were grabbing my ankles and pulling me down and down, ever deeper, through the decay of sludgy silt and towards the centre of the this languid, lily-padded pool.

Oak, my faithful friend, panicked (as usual) and assumed I was drowning. Barking wildly to drive the ghouls away, he swam around me in ever decreasing circles, scourging my skin with his frantic claws, unable to understand why his rescue attempts were not, Lassie-like, treated with appreciation!

I lay on my back and floated in sorrow, in a pool of self-pity.

Eyes closed … the minutes drifted by … perhaps longer, until I was shocked back to life by the sound of Oak shaking on the shore and a shaft of sunlight striking my skin.

Eyes flashed open.

The fog was lifting and now the quarry was all about me. A few strokes led to the shallows, where I stood bare and basking in the Autumn warmth, watching my skin ripen from white to blue to pink, wrinkles unfolding like a juice-plumped fruit.

A smile broke across my face, mood rising with the mist, as I inhaled the barren beauty of this place.

I recalled how many times I had explained the ‘seasons of life’ to my patients; likened the ups and downs to the ebb and flow of tides, the waxing and waning of the moon. “Even the darkest of days will end – the light always breaks through.”

And suddenly there they were.

Legs.

Five to be precise – three wooden and two very human.

Glancing up towards a green tufted outcrop I spied an easel, a canvas and a woman – looking straight at me, head tilted, sable brush in hand.

She was smiling too.

We exchanged a knowing acknowledgment.

I had been painted in all my colours …

You should’ve been a writer but I’m very glad you were my doctor

LikeLike